NEMESES: SELECTED COLLABORATIONS 2014 - 2019

Available to buy https://www.haverthorn.com/books/nemeses-selected-collaborations-of-sj-fowler-volume-2

293 pages / £11.99 / October 2019.

Scroll below for videos, publications and news related to NEMESES

My most ambitious book, nearly 300 pages of collaborations, in text, fiction, poetry, music, photography, film, sculpture, performance and everything in between. The book is a testament to what I’ve tried to do with a base in poetry and an ambition to learn and grow as an artist through the brilliance of others. It is a really special volume, wonderfully supported by Haverthorn Press, who have rendered the huge volume of works into a beautiful, cohesive tome.

From the publisher “No poet-artist has ever explored the potentials of multidisciplinary collaboration as thoroughly as SJ Fowler and Nemeses is a landmark publication evidencing that exploration. The book brings together over 50 collaborations and collaborators, placing poems and prose alongside musical scores, diaries, sculptures, films, photographs, scripts and more. It explores not only the grand potential for collaboration as an innovative, generative, playful and profound practise, but also aims to expand what is possible when sharing the live upon the page.”

Launches - five events in October and November 2019, click the link for videos and pictures, or scroll down

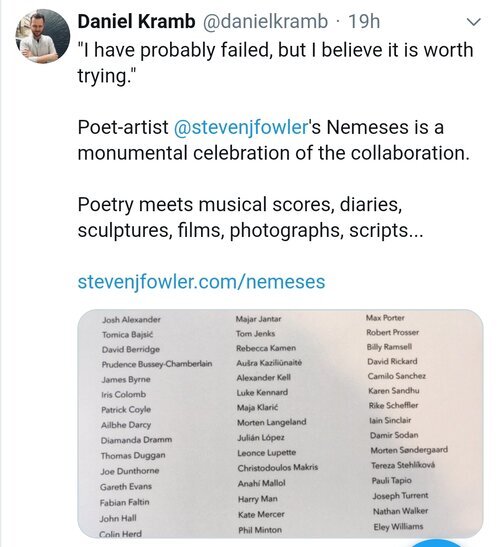

The book includes the following collaborations and collaborators :

Your flowers won’t grow or... with Karen Sandhu

The Best Poet Award with Max Höfler

Myth of the Mole with Max Porter

Soundings with Phil Minton

Subcritical Tests with Ailbhe Darcy

Returnings with David Rickard

It Is What Is Love / It Is What Is Hate with Rike Scheffler

Iceland with Joe Dunthorne

The Gold Nanorod and The Silk Fibroin with Thomas Duggan

Oberwilding with Colin Herd

Animal Drums with Joshua Alexander

Animal Drums (Prompt Note) with Iain Sinclair

Stalker with Harry Man

Beastings with Diamanda Dramm

A Soul Referendum with Iris Colomb

Funicular with Luke Kennard

The Next Step with Fabian Faltin

The Irish Character Study with Billy Ramsell

House of Frens with Alexander Kell

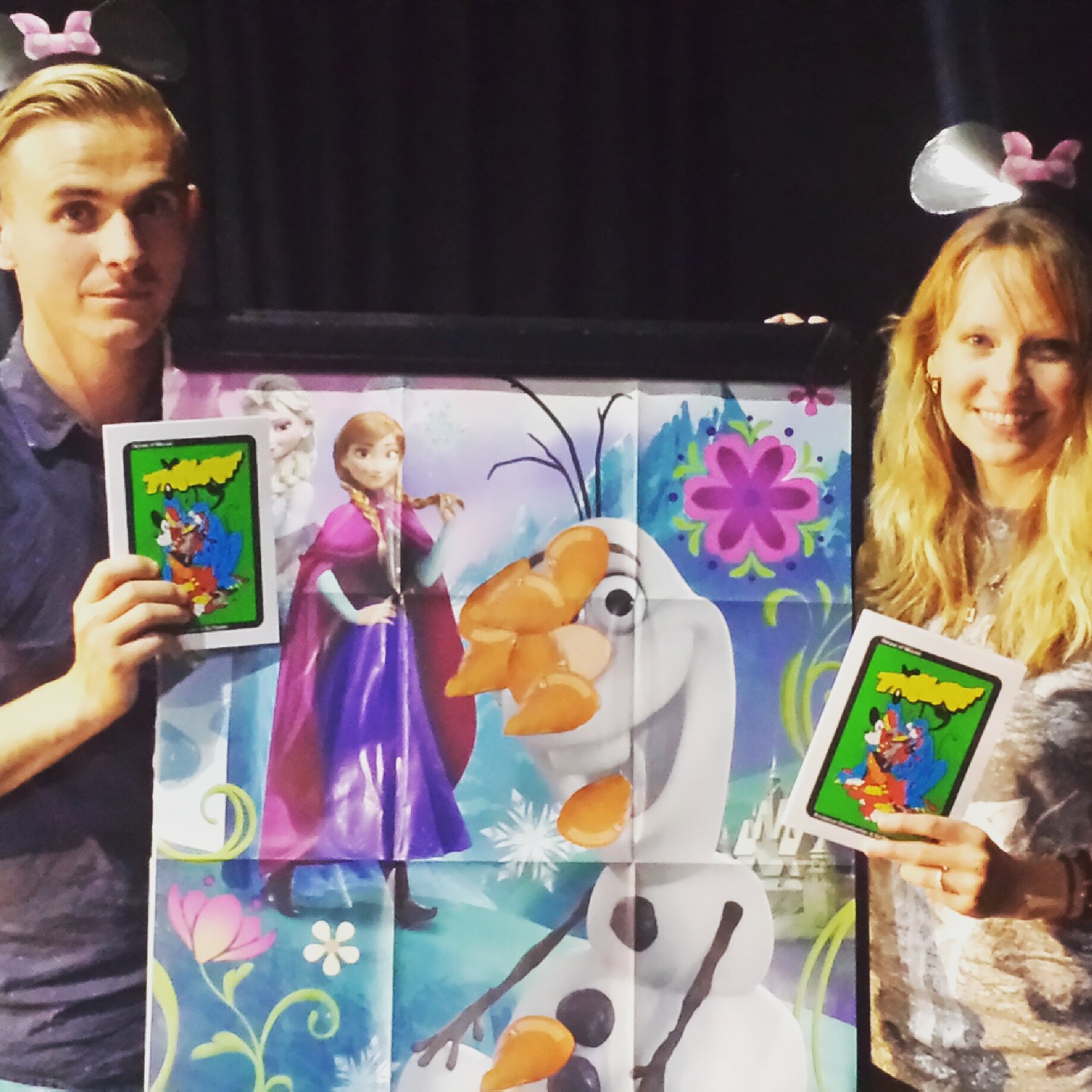

House of Mouse with Prudence Bussey-Chamberlain

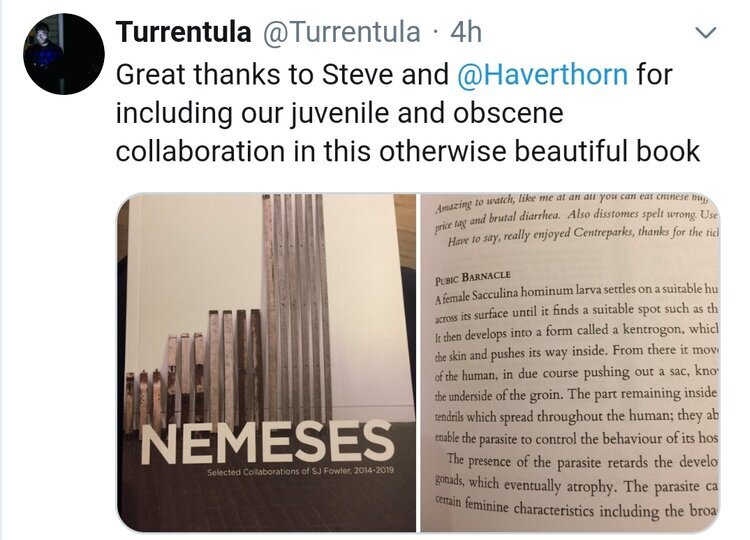

Parasites of the Symbiocene with Joe Turrent

Worm Wood with Tereza Stehlikova

The Bleeding Eyes with Eley Williams

Hannah Fought with Nathan Walker

The Waterwalk with Krišjānis Zeļģis

The Sparrow Egg in a Chocolate Nest with Shimon Adaf

The Singing Bridge with Claudia Molitor

Lunalia with Maja Jantar

133 Proverbs with Tom Jenks

The 7th Poet with John Hall

Enthusiasm with Noah Hutton

{Insert Meaning Here} with Morten Langeland

Detonations with Yekta

The New War Machine with Christodoulos Makris

The Venetian Poems with Ariadne Radi Cor

Neprijatelji : a group poem made in Croatia

An Infinite Family a group poem made in Argentina

Forty Feet with David Berridge

Ibunka with Zuzana Husarova

We Could Try with Pauli Tapio

Constellations with Rebecca Kamen

Bristol with Patrick Coyle

Adventures in Metaphysical Translation with Robert Prosser

The Night-Time Economy with Kate Mercer

I’m Picking Heads of People with Ausra Kaziliunaite

When the Rules Keep Changing with Camilla Nelson

Open Mouth Surgery with Morten Sondergaard

On the book : It is always in compiling Nemeses that I really realised how many collaborations I have undertaken in the five year period the book covers. It presents excerpts of full collections alongside works made specifically for Nemeses. It draws from full feature films, exhibitions, commissions, installations and poems made for performances around the world. The book is finished with an essay which details, in basic terms, how it was constructed and what my thinking has become around poetry and collaboration.

Forming transitory but generous communities : a review by Robert Sheppard

http://stridemagazine.blogspot.com/2020/04/forming-transitory-but-generous.html : April 1st 2020

This is a difficult book to review because, although it is easy to say this is a volume of collaborations by SJ Fowler and many others, it is not easy to delineate the types of collaboration involved. Anybody who has attended the hundreds of collaborative ‘Enemies’ events curated, and participated in, by Fowler wouldn’t be too surprised by this, but Nemeses is not just a selection of the experimental cabaret duos of those performances, important though they have been, but a presentation of samples of many collaborations in various media.

You will find literary collaborations of many kinds, from Oulipo experiments and ‘translations’, to ekphrasis of artworks or films, through what look like extemporised wordplay texts, to collages of found sources. There are even some lyric moments. There are co-authored proverbs, diaries and journals, micro-fictions, absurdist texts, and fake public information documents. Many are manifestly the results of dialogic to and fro responses, some even maintaining the form of letter and email exchanges. There are sketches and playlets (often for two voices and often very funny), as well as polyphonic poems for multivoiced delivery. There are speculative instructions for performances, as well as photographic and linguistic documentation of actual performances, whether for voice(s), dance and wrestling, sometimes involving visual art and/or music, and occasionally without words at all. There are visual poems exploring neurodiversity (of the variety dubbed by Fowler the poem brut). There are representations of artworks and sculptures that incorporate texts by Fowler. There are stills from films accompanied by notations of the films’ narrative or action. There are text and photographic collaborations. There are conceptual texts for and about conceptual performances. There are notes from psychogeographical dérives (with and without visual evidence). There are excerpts from book length coauthored publications, already in the public domain, alongside short one-off collaborations, seen here for the first time. There are nearly 300 pages of this.

The collaborators are also suitably varied, as might be expected from Fowler’s often unusual pairings for the ‘Enemies’ performances. Fowler works with some elite figures, such as vocal artist Phil Minton, or novelist Iain Sinclair. There are ‘names’, such as Sandeep Parmar and James Byrne, emerging artists like Eley Williams or Ailbhe Darcy, but there are many lesser-known figures here, which suggests Fowler’s generosity, and many European authors, which underlines Fowler’s internationalism (intensified after Brexit), as well as to the non-native speakers’ willingness to risk work in the bastard language of our insular isle, for example, Ausra Kaziliunaite and Robert Prosser. Tom Jenks, Harry Man and Christodoulos Makris are frequent partners for Fowler. Luke Kennard, Camilla Nelson and John Hall are less so. In all, there are 54 collaborators (and I’ve mainly named only writers above), a promiscuous bunch.

I found the book an exhausting but exhilarating read (or ride). One of the delights of creating collaboratively is the opportunity to produce work that could not have been made in any other way, and which is not like work produced individually. Artists here vary in their abilities to ‘let go’ (Sinclair unavoidably sounds like Sinclair) but there is a general willingness to surrender to the encounter (particularly where performance is part of the works’ realisations). In a postface, Fowler quickly passes over the usual reason for collaboration as a concept: collegiate sharing disrupts the loneliness of the long-distance writer. He notes: ‘I have proofed my concept with others, forming transitory but generous communities which have supported the making of challenging and complex work, live, and it has taken me on an extraordinary personal journey.’ He admits, also, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, that the whole endeavour is ‘selfish’: ‘I have somehow mitigated defeat in my other works by constantly working with others … collaborating has left me smug’! Success has been snatched from the jaws of his collaborators. What strikes me as interesting is that there are 54 other poetics of collaboration lurking in this volume, none spelt out coherently like Fowler’s, of course, but each interacting in various ways with his. I want to leave the poetics to one side and plunge into two sample offerings, one a collaboration across media, the other what I call a ‘literary collaboration’.

‘Beastings with Diamanda Dramm’ ends with a timeline of Fowler’s collaborations with the Dutch violinist and singer. In it, he repeats his ‘smug’ thoughts about collaboration quoted above, and accounts for their four meetings and works. Dramm seems to have set pre-existing poems by Fowler to music, although he says: ‘DD made them better by cutting them up into smaller, newer chunks and singing them’; she characterises this as ‘making a mini opera’. This work is (partly) about a killer chimp, and will be available on CD. What this book contains is three startling delay photographs of Dramm’s performance at the Bimhuis (Fowler is surprised how famous she is in the Netherlands) with Fowler’s visual poems projected against her, a barefoot figure in a long red dress streaked with black or blue forms, vertical tendrils. It also contains a couple of texts, though it is difficult to see where they fit in with the timeline. The second is a long processual piece, ‘A Clever Trick Memorising This You Played’, which begins: ‘your words sound better when my words are put through your words’. This suggests the piece was narrated or sung by Dramm from memory and that it describes its own verbal compositional processes. The lines metamorphose into ‘a word sounds wetter when your words are out of my words’. In the next line, ‘words’ has become ‘worms’. Eventually the text is in different territory altogether: ‘freeing tampon seems bloodier when you are tickling the red loom’. This reader is left wishing he’d been an audience member, a witness to the unfolding processual phrases, sung and set to violin playing.

In reading literary collaboration on the page, the reader often has recourse to a peculiar binary refocusing that feels like a lack of focus. That’s because the flow of the writing is continually interrupted by itself, by the switch between writers. (Imagine two drivers switching at the wheel of a truck, without stopping.) In some cases, where the dialogue is not visible, you stop trying to guess who wrote what. This, I believe, is a sign of success. It hasn’t achieved a third voice (a term which is based on identity of writers not on the identity of writing), but it could be said to leave a linguistic trail coherent enough to regard as a single discourse.

In ‘Sleeping Beauty’ with Prudence Bussey-Chamberlain (from the book House of Mouse) you can see this in action. A Disney film, not the original fairytale, is deconstructed (though deliberately misread might be a more accurate term) by the two writers, interpolating modern idioms as they go, with their ‘slept upon beauty’:

It begins when her spinning

is cancelled; no one can spin

the risks

of being awoken

the poem says, playing on the political meaning of ‘spin’. Sleep is her protection. The Prince is

… named after

the king of

who has also braced

himself in the ikea

togetherness of

a plastic lake holiday

package,

horse-ride

incl.

with future marriage / love / awakenings

which turns him towards the bourgeois average. He’s ‘the king of’ nothing much. No wonder

beauty says yes to the dress

it is the only affirmation that is

your own

aside from sleep

Sleeping Beauty has little beyond her name, her place in other narratives, Disneyfied or not.

There are plenty of other pleasures in this book. SJ Fowler, never smug, despite his self-identification, has extended his own practice, to be sure, with these interactions, but it is difficult not to think that the collaborators also have extended their practices. As you read this book, you feel collaborative potentiality turning to imaginative growth. That’s a rare thing.

© Robert Sheppard 2020

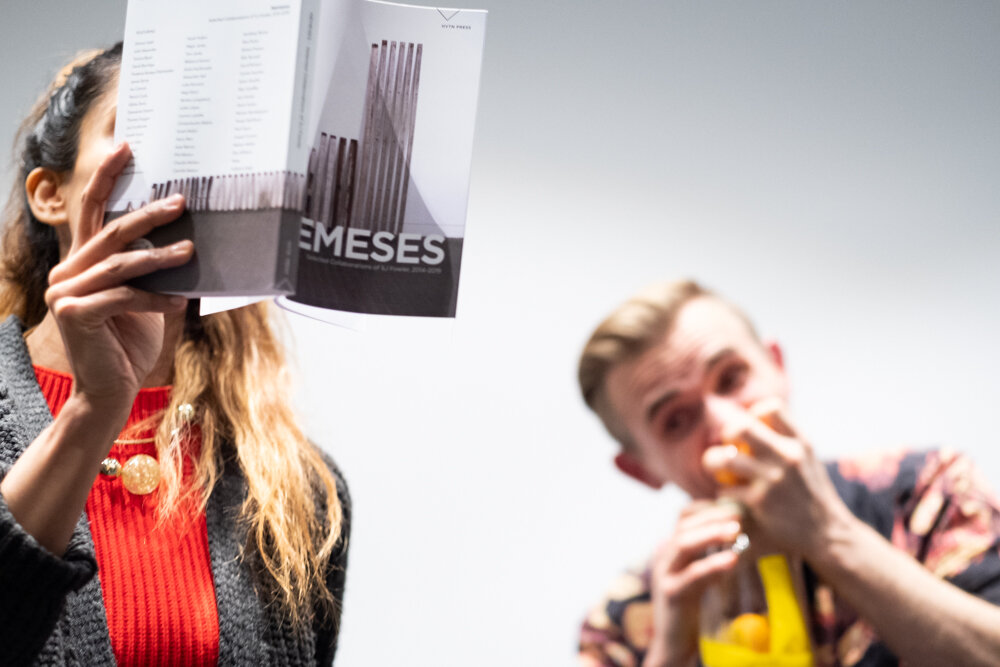

Nemeses : book launch I - St Johns on Bethnal Green, London

October Saturday 26th 2019

A poetry book launch like no other. Nemeses was launched at the remarkable gothic St John on Bethnal church, on a windswept night of poetic performance and shenanigans. I read with nearly ten collaborators, performing works from the book Nemeses, or presenting performances that related to the printed collaborations, or that toyed with the context of the reading, the concept of a poetry event and improvisation. The evening's readings was revealed like a meta-play, led by anti-host Harry Man, and so accumulated its full effect (disappointment) over the entire night, hence the deliberate intervention of the host about each duo reading. I read with SJ Fowler and Joe Dunthorne, Eley Williams, Ailbhe Darcy, Luke Kennard, Prudence Chamberlain, Karen Sandhu and Harry Man

Wonderful pictures by Madeleine Rose http://www.stevenjfowler.com/blog/2019/10/29/a-note-on-pictures-from-nemeses-launch-by-madeleine-rose

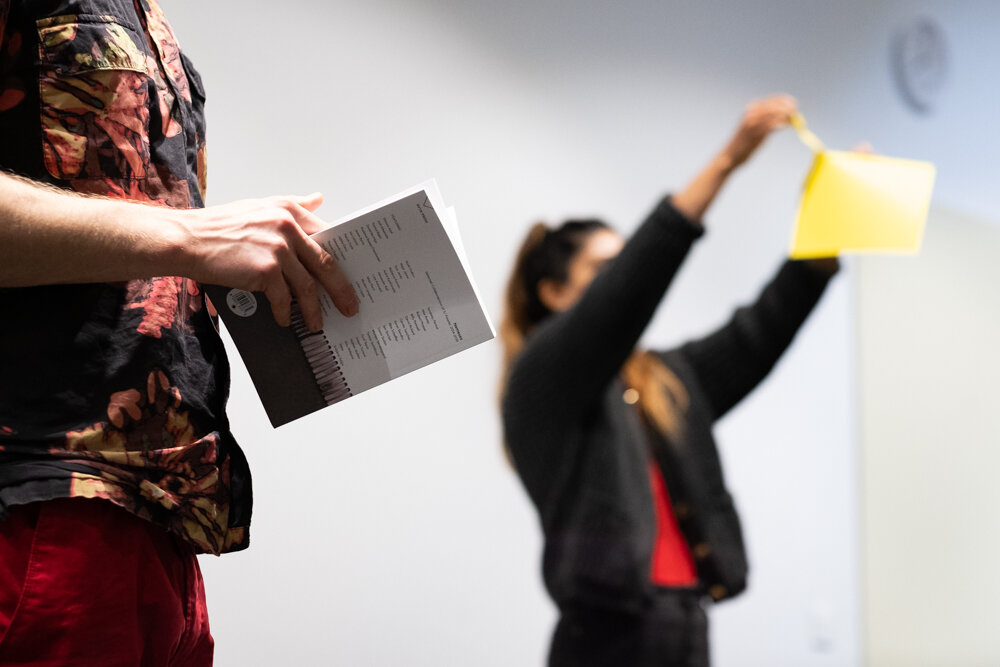

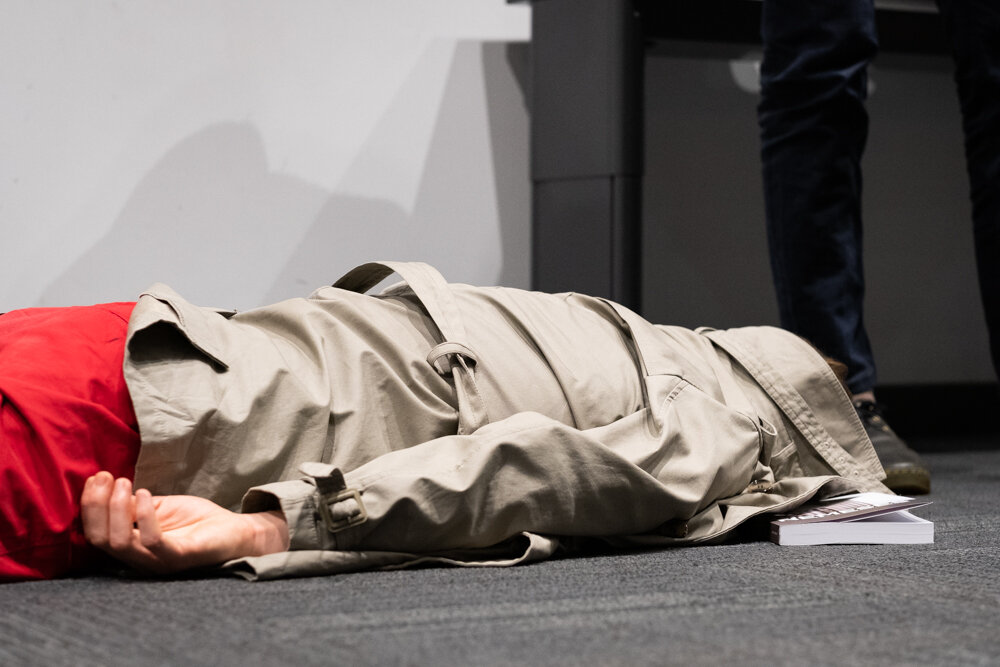

Launch 2 : Nemeses in Kingston for Writers Centre Kingston November 5th 2019

The second NEMESES launch, this time in Kingston upon Thames, performing collaborations with two contributors collaborators Karen Sandhu and Joseph Turrent. Two very contrasting performances, one about parasites and my live death, and the other about oranges, and perspective, and jars, and my live death.

more brilliant pictures by Madeleine Rose http://www.stevenjfowler.com/blog/2019/11/8/a-note-on-performing-with-joseph-turrent-and-karen-sandhu-for-nemeses-launch

Launch 3 : Nemeses in York for York University : November 6th 2019

Generous of York University and JT Welsch to host a launch of Nemeses, which was basically an hour long meta-performance with meself and Colin Herd, Prue Chamberlain Bussey, Harry Man, Tom Jenks and Nathan Walker. All these brilliant poets and artists are in the book, of course, but Harry Man was the anti-host, bewildering students with interruptions, and then the collaborations ranged from gift giving ceremonies to neverending introductions to sound poems to makeup application. It was weird and good. And we finished with a Q&A, which was actually lovely. We then all departed for dinner, after washing our faces. A lovely experience, as I always have when reading in York.

Launch 4 at Rich Mix for Poem Brut : November 9th 2019

The poem brut was as it always seems to be, teeming with new people and ideas in a space and place that felt communal and generous but where proper intense and weird work was shared with a seriousness and play in balance which i am proud i somewhat curated. See all the videos and they are worth seeing www.poembrut.com/richmix and I launched my NEMESES book again but this time alone, or self-partnering, until a mole helped me.

Launching Nemeses book launch 5 at Small Publishers Fair, in Conway Hall : November 16th 2019

A brilliant way for me, personally, to end a wonderful experience, as it always is, at the Small Publishers Fair, brilliantly run by Helen Mitchell. So many people in Conway Hall over these two days are friends or people who have actively supported my often quite distinctly uncommercial work. They do so generously and often against their interests, I think, so I see these fairs as an opportunity to thank them. I always try to visit every table, meet as many new people as possible, and say thanks to those I know, and buy books. This year I had the chance also to have the last launch of my selected collaborations, NEMESES, with haverthorn press, by collaborating with my friends and peers I admire, Eley Williams and Phil Minton, both of whom are in the book naturally. I felt quite content, liking them so much, and liking the fair, and conway hall, to have the chance to do this, and I also realised that what I felt was that it is something that I can transition from a literary reading with Eley rooted in her wit to a fully improv free music vocalisation sound poetry piece with Phil, quite comfortably. In fact, perhaps my work is the space between those two things, both powerfully and obviously literary and poetic to me, but on the surface, for the poor audience, clearly radically different.

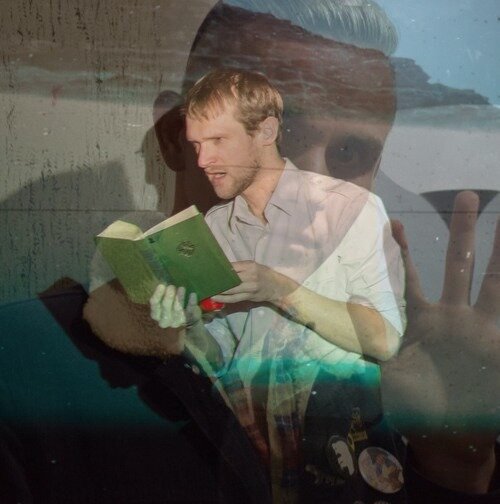

ENTHUSIASM -a film (with Noah Hutton) November 18, 2019

Enormously generous of the brilliant Hotel Magazine to host, and premiere, my film made with Noah Hutton (Noah made the film, edited it, and I think conceived it. I wrote it, starred in it, and watched im work, to learn) https://partisanhotel.co.uk/Noah-Hutton-SJ-Fowler

A short film—a transatlantic cinematic collaboration produced as part of The Hub residency at Wellcome Trust—Enthusiasm draws on new techniques in analyzing internal monologues and self-consciousness used by contemporary neuroscientists. Utilising the possibilities of cinema to reveal the conflicts of inner and outer narrative, how our internal and external languages collide, the film features improvised and acted scenes alongside voiceover techniques, to juxtapose that which is said and that which is thought. The text featured below is the latter.

The film being published / premiered / hosted by Hotel is the second of their very generous features on my collaborations to help share word of my selected collaborations NEMESES with Haverthorn press https://www.haverthorn.com/books/nemeses-selected-collaborations-of-sj-fowler-volume-

A note on : Christodoulos Makris & others on NEMESES November 8, 2019

http://yesbutisitpoetry.blogspot.com/2019/11/nemeses-by-sj-fowler-collaborators.html ….

Steven writes: "It is always in compiling Nemeses that I really realised how many collaborations I have undertaken in the five year period the book covers. It presents excerpts of full collections alongside works made specifically for Nemeses. It draws from full feature films, exhibitions, commissions, installations and poems made for performances around the world. The book is finished with an essay which details, in basic terms, how it was constructed and what my thinking has become around poetry and collaboration."

Our text for 'The New War Machine' is edited from transcriptions of two semi-improvised collaborative performances enacted as part of the Arts Council-supported Yes But Are We Enemies project and 10-day tour of Ireland and London that I produced and co-curated with Steven in 2014 - the performances in question happening in Galway Arts Centre on 21 September and Rich Mix Arts Centre, London, on 27 September of that year.

Additionally, I'm proud to have played some part in a producing, curatorial or editorial capacity in bringing about or supporting some of the other collaborations featured in Nemeses: 'Subcritical Tests' with Ailbhe Darcy began at Yes But Are We Enemies and culminated in a book-length project which then became the first Gorse Editions title we published, in 2017; 'It Is What Is Love / It Is What Is Hate' with Rike Scheffler is also forthcoming in gorse No. 11; 'Beastings' with Diamanda Dramm is the result of a collaboration that began after Steven and Diamanda met at Phonica: Eight in March 2018 (where they performed storming individual sets) and with a full album release forthcoming later this month; and 'The Irish Character Study' with Billy Ramsell was conceived & performed as part of Yes But Are We Enemies.

You can read Steven's introduction to Nemeses on the gorse website. The book is available to buy from HTVN press.

GORSE publish my opening comments to how NEMESES was rendered : Oct 23rd 2019

http://gorse.ie/the-static-the-live/

“The relationship between the static and the live is akin to the relationship between the heard word and the read word. It’s similar even to that which is experienced and that which is remembered. Obvious as this may be, a hierarchy in the language arts of poetry, fiction and text in general, favours the written over spoken. Marks upon the paper are the dominant article because of their possible permanence, and their fixed place in time. The sounds or experiences are secondary. I’m understating the issue, historically and philosophically, to make my first explanatory apology……………………………”

HOTEL publish my collaboration with Joseph Turrent, taken from NEMESES : Oct 21st 2019

https://partisanhotel.co.uk/SJ-Fowler-Joe-Turrent (it contains my obituary)

PENIS-EATING LOUSE : The penis-eating louse enters male humans, typically aged 18-39, through the anus. It severs the blood vessels in the prostate gland, causing the erectile tissue to fall off. It then attaches itself to the remaining stub of the penis and extracts blood through the claws on its front [clarification needed] causing the penis to atrophy from lack of blood. The parasite then replaces the penis by attaching its own body to the pubic bone. It appears that the parasite does not cause much other damage to the host, but it has been reported by Lanzing and O’Connor (2074) that infested men with two or more of the parasites are usually underweight. Once the parasite replaces the penis, some feed on the host's blood and many others feed on human mucus.

POETRY MAGAZINE publish my collaboration with Max Porter, taken from NEMESES : Oct 1st 2019

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/150930/myth-of-the-mole

“I say mole, I mean Sharpe, Sean Bean as Sharpe, I mean people are dying while you go full-bore Cockerhoop. I mean it wasn’t like that when I was around, when I was younger. I mean a certain kind of touch, of look. I mean a freedom pass. I mean blindness to the estate. I mean, have you been in prisons, lately? They don’t really. I mean you aren’t talking of who fixes what you’re using?

There’s an audio recording available free online too, of Max and I reading the poem https://www.poetryfoundation.org/podcasts/151173/myth-of-the-mole

Robert Sheppard on Collaboration and Nemeses #3 - Camilla Nelson collaboration text

https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2020/04/thoughts-on-collaboration-11-steven.html Monday, April 06, 2020

It’s time to examine the collaborative practice in Fowler’s projects in detail. (You need to read the previous posts, really; see the link at the end of this one.) ‘I have proofed my concept with others, forming transitory but generous communities which have supported the making of challenging and complex work, live, and it has taken me on an extraordinary personal journey,’ Fowler says. The ‘challenging and complex’ work I want to examine is also a short one, ‘When the Rules Keep Changing’, written with Camilla Nelson.

I know Camilla, having met her at conferences, always at Bangor, now I think of it, but I don’t really know her ‘own’ work well, beyond a number of isolated poems and witnessing her in performance. I have two of her books on order, and both have taken longer than one would expect to arrive, but I can’t wait any longer to get on with the next part of these ‘thoughts’. I’m also having to wait until Rupert Loydell publishes my review of Fowler’s ‘collaborations’ on April 1st to post these ancillary ‘thoughts’, but I am writing them well ahead of their appearance. (I’m trying to keep the ubiquitous coronavirus at bay as I do: as I said on Twitter: 1st April is literally unthinkable from where I sit.)

‘When the Rules Keep Changing’ is a three page text in two columns, the left-hand one of short, irregular, conventionally punctuated lines, in classic free verse lineation, absent of stanza shape. The right-hand poems consist of longer lines, utilising phrasal caesura, spatial syntax, with minimal, but not absent, punctuation. Internal openness is held in the frame of three 12 line stanzas. The left-hand text asks, at one point, ‘are you cold enough Camilla?’ but we cannot simply infer that this was written by Fowler, since the voice is a feature of a particular situation to which I will return, in which the question is posed. It may be a quotation or an imagining. Neither can we assume that any of the verses are the sole work of one or the other co-authors. (My own collaborative practice of covering the tracks of authorship, most radically in Twitters for a Lark – see here – alerts my awareness of this possibility: https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2019/03/my-ref-statement-describing-twitters.html

The nature of the self is at issue in both the first lines (and that stands whether you read the left or the right-hand text first, the left being positioned lower on the page than the right. I’m now going to privilege our conventional left to right brain programming!). The left-hand text opens:

Why would I tell a simple

story of myself

to a room of strangers? (p. 269)

which questions self-exposure, and recognises that ‘telling’ is alienated from the self that is told, and evades the complex contemporary realities Fowler’s poetics embraces (it may also embody misgivings about the self-revelation that public performance entails. Geraldine Monk is very good on that, here: https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2013/12/the-tildes-outside-language-were-not_14.html

The single, singular, voice questions love and safety, self-obsessively, but ends by

Trying to let things go, to be kind

out of choice and not fear,

inhibition, introversion, eticence, wariness, caution, suspicion, misgiving, mistrust (p. 269)

(Surely ‘eticence’ is a typo for ‘reticence’? I didn’t say so in my review, but there are more typos than there should be in a book of this quality.)

The long line which invades the empty space under the right-hand text, and is an image of the thoughtless impositions of self-enclosed personhood, is a list of inwardly-looking, even ‘selfish’, to use a term from Fowler’s poetics (‘the whole endeavour is ‘selfish’, I summarise, in my review), self-conscious (but not negligent, let’s not overstate it), negatives. At least the passage continues and ends: ‘or laughter’, which is one of the joyful antomyms of the long line’s list. It is almost as if the rhetoric of this voice embodies ‘the unitary vision of the subject as a self-regulating rationalist entity’ (p. 211) that Rosi Braidotti bangs on about. (Idea, the muse of Bad Idea taught me her post-Deleuzean (or should that be most-Deleuzean?) thought. https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2020/01/robert-sheppard-links-to-all-six-bad.html

But it is also tempered by the possibility of laughter.

The right-hand text opens with a contrary view of self, even pleads to the other: ‘be my mirror’, but refuses the singleness of self: ‘show me my many selves’. It is as though the self-enclosed subject is countered here by what Braidotti calls ‘the nomadic vision of the subject as a time continuum and a collective assemblage’ (and we will come back to her notions of collectivity to describe collaboration itself). (210) The right-hand text espouses the role of ‘shape-shifter name-changer’.

Metamorphosis is form. The text is likewise less of a first-person narrative, although the signature line, ‘I can’t play the game when the rules keep changing,’ expresses a ‘wariness’ towards game-changers rather than name-changers. It also questions ‘the game’ of this self-mirroring text, which is itself an image of (this) collaboration. Perhaps there are issues to be explored before we simply quote Rosi again, with her sense that the first person plural is party to the mantra: we’re ‘all in this together’ (Braidotti’s words stick a little in my throat after Cameron’s austerity hard-sell in our Age of Immiseration. And now Trump’s just tweeted it too, about coronavirus, the ‘Chinese Virus’.) She says: ‘Our copresence, that is to say, the simultaneity of our being in the world together, sets the tune for the ethics of our interaction with both human and nonhuman others.’ (210). That seems to me a model for collaboration, generally. The right-hand text continues (and ends this section, its ‘turn’), the voice suspecting that its shifting positioning (it is difficult to assign gender here) is compromised by the egoic stasis of the addressee:

You’ve shown me the shape of your treasure,

told me why she’s hidden trust in a locked box. (p. 269)

There is dialogue here, at the textual level (where we read), and at the compositional level, though there is difference and distance, revelation (‘shown me’) and concealment (‘locked box’, trust/trussed).

In the second section (perhaps I should also have said each section is a page) the texts begin simultaneously, by which I mean they both start on line one, though Western reading will privilege the left. This is another first person script of mild dejection that picks up on the ‘trying’ liturgy at the end of its part one:

Trying to understand the love

of those who cannot give it,

like a screwdriver. (270)

It’s an odd simile, but one that emphasises violent gesture (with the dual sexual and exploitative connotations of ‘screw’), but what is being attempted to be understood is a paradoxical withholding of love: love exists, sure, but it is retained, a stagnant reservoir, in the self. The voice itself speaks with a daring combination of violence and tenderness. The narrator says, ‘I’m also ready,/ all jaws’, like you might say ‘I’m all ears!’, ‘with a kindly fire/ with freedom of movement’. (270). This only amplifies the ambivalence of part one, already noted. The dichotomy is repeated (‘hand-made weapons/ technology of love’). Violence to the self tempers this readiness for engagement (there’s a mania for it, almost). Of course, this poem is written for a performance in 2016, and that might explain the desire for ‘freedom of movement’ differently: that resonant phrase is one of the dull bureaucratic notions that became illuminated by contention during the Brexit debate of the same year. Inward negative energy battles against a will towards community and copresence, literally bending in the last words of this section: ‘Its [sic] just angry infolding, with a clinch. /The inclination towards tactility’. (270) (Odd to write that in the Age of Social Distancing.)

‘Tactility’ would be a useful noun to summarise the focus of the right-hand poem, though focus might not be the best word for this more dispersed discourse (it’s clearly a collage) though we do read a first person voice: ‘Only once your hand’s around my wrist can I begin to feel/ skins lie different’. (270). The poem is alive with sensation (with a slight threat that echoes the violence this poem is answering to its left, as it were). We sense a realisation of bodily movement, or rather, of the bodily (‘you offer me your body/ to lie down in’)) (270), slightly sexualised, and movement, or rather dancing and swimming (which again has its edge of danger): ‘the shimmer and dazzle mask the drowning.’ (270) There is less attempt at coherence in this more fragmentary discourse, but like its predecessor, it returns to a sinister image of containment, ‘a long-locked room’. But there is more hope in freedom of movement than in its ‘mirror’ poem: ‘These walls I’ve worn down once before.’ (270) Although that also suggests that previous attempts at accessing copresence have failed (or at best were attempted before).

Section three’s left-hand text immediately picks up on (responds to, in one of the first evidences of direct to and fro, in this sequence) this penetration of barriers. It is a nightmare, with both surprise and reversal:

The room darkens,

a head emerges through the wall,

though your door is open.

It is a dog’s head

and it asks,

are you cold enough Camilla? (271)

The intrusion of the first name is almost a refutation of the multitudinous self that claims to be a ‘name-changer’ (269), an attempt to pin the building sense of movement down. (Do we even think: this is Fowler addressing Camilla? Is this a recognisable dialogue now, in the same way that Alan Halsey and Kelvin Corcoran address one another in Winterreisen? See here: https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2020/02/thoughts-on-collaboration-or.html

The door is open, so the mural penetration is unnecessary, and turns out to offer this interrogative canine with its intrusive, but not completely understood, question. The single, authoritative, certainly male, possibly masculinist, voice, promises, ‘If you come with me,/ I can get you out of here.’ (271) But he knows he’s defeated: ‘You ignore it and fall asleep./ Once shy, twice bitten’. (271) Amid this hint of Sleeping Beauty (we are back with Fowler’s collaboration with Chamberlain; see my Stride review), there is a hint of projection here, rather than mirroring. These are lines that the narrator might easily apply to his own ‘cautious’ self-hood, although the biting actions remind us of the readiness of jaws announced earlier. Such a strategy makes for special pleading, bordering on emotional blackmail, masquerading as fairytale transformations: ‘The wilderness only seems beautiful/ when you’re visiting’. (271) At least the self-withdrawal of the left-hand poem is countered by a desire for the copresence of the other, although the ‘wilderness’ is rendered ‘hideous’ by the addressee’s absence, or rather, by her immobility (‘if you’re stranded’).

This antagonism (combined with self-doubt) reflects the poetics that Fowler expresses, even in the name of project and book: ‘enemies’ and ‘nemeses’, and the way copresence or coauthorship snaps back onto the ‘selfish’ motive for the act. ‘Collaborations are a means of friendship, yes, and they are an innately social act of writing… But they are really just about ourselves. Collaborations are really just mirrors rather than procreations.’ (283) ‘Be my mirror’ is an invitation advanced in this text, but rejected. After all, ‘I can’t play the game when the rules keep changing.’ (269)

This is a game whose rules keep changing because of the nature of the incessant, insistent, dialogue: ‘Red riding hood Snow White The hunting ground.’ (271) The undercurrent of fairytale imagery - openly female in orientation – is thus brought to the surface, explicitly, in this first line of the final right-hand 12 line stanza, only to be rejected, in the only first person plural in the text: ‘We’ll not write fairytales or nursery rhymes.’ (271) This could also be the voice of a collaborator trying to establish some stable operational rule with the other collaborator.

You ate the apple after asking.

But that’s not how the story goes.

You’ll not be made the villain of the piece. (271)

This is a strong act of refutation of pre-set narratives (Snow White probably, The Book of Genesis, re-gendered, less so). It refuses victim-status to its addressee (whose ‘psychology’ we’re familiar with by now). The section (and the poem) ends with an image of asserted knowledge and safety:

the birds

have eaten all the breadcrumbs but I know the way.

Held close kept safe. A flame stilled long enough

The movements of the ‘game’ of the whole coauthored poem’s ambivalent adversarial gestures are brought to temporary pause ‘long enough’ for illumination. The rules of the game of collaboration have stopped because the collaboration is over (to again read the text as a meta-commentary on its own composition, perhaps a projected prediction of its ultimate performance).

*

This is a fairly in-depth reading which (like most such close readings) leaves untraced trajectories that other readings will (or could) pick up on. You could sensibly ask: ‘Are there two narrators in this text, or not?’ and a whole list of other questions might arise. Somebody else might register how much they enjoyed the text. I do, too, but I don’t say that above. Perhaps more of you will consult the original. Much of the above won’t be used in my eventual article on collaboration, though I am pretty sure I will comment on this work.

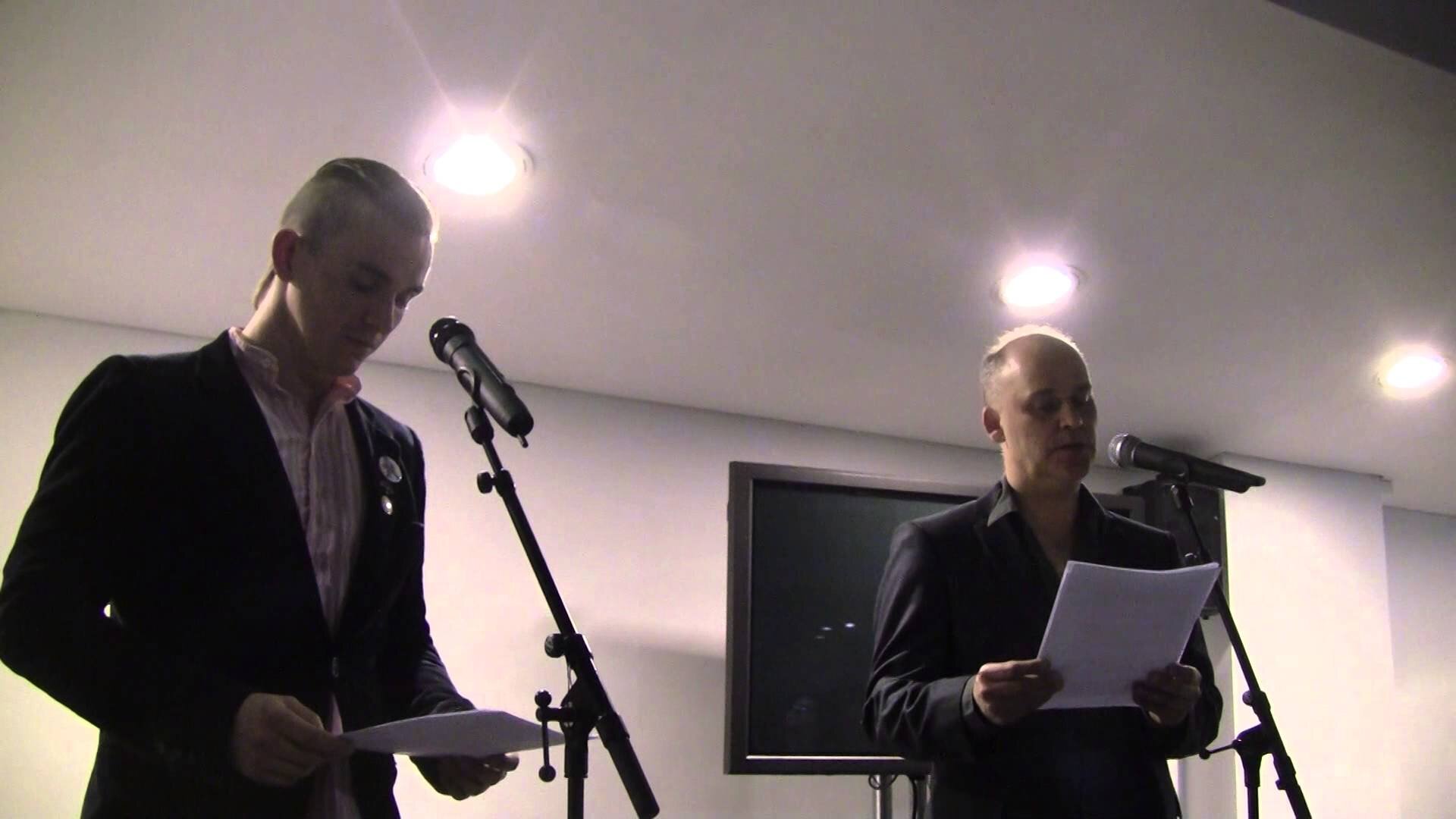

Imagine it read ‘live’: the two columns perhaps read in turn in two monotones, by two rigid, fixed, bodies, tentatively clutching their microphones, and mumbling away in the contemporary ‘poetry voice’ that is probably learnt from records of Philly Joe Larkin. ‘Hideous’ as a fairytale wilderness!

Of course, anybody who has read this text will know that there are two photographs printed under the second and the third poem: Fowler lifting up Nelson and Nelson on Fowler’s back, respectively! (270-271) They are still shots of the performance of the piece by the two authors, and gesture towards the ‘live’ element that is essential for Fowler, ‘challenging and complex work, live,’ as he accurately puts it.

They point us to the extraordinary video of that event. See it (and you) next time, in a couple of day's time.

All posts in this ‘Collaboration’ strand – there are now 10 others, an interlude, and links to associated reviews on other blogzines – may be accessed via links on the first post, a hubpost, as I call it, here:

https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2020/01/robert-sheppard-thughts-on.html

Robert Sheppard on Collaboration and Nemeses #4 - Camilla Nelson performance

https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2020/04/thoughts-on-collaboration-12-steven.html

In all these ‘thoughts’, I alert readers to the fact that it is part of a strand (15000+ words now) concerning collaboration, and I ask people to consult the hubpost, which lists (and explains the focus of ) each post, here: https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2020/01/robert-sheppard-thughts-on.html However, today’s post cannot be properly be understood without at least looking at ‘Thoughts on Collaboration 11: Steven Fowler with Camilla Nelson (reading the text)’, which offers a close reading of the text ‘When the Rules Keep Changing’, which Fowler wrote with Camilla Nelson. READ THAT HERE.

Their performance of this is part of the South West ‘Enemies’ Poetry Tour, a reading on August 6th 2016, at Bath’s Literary and Scientific Institution. The call for participants (https://www.theenemiesproject.com/southwestcall ) gives an idea of the tour and reveals (something I hadn’t clocked) that Camilla Nelson’s press Singing Apple, was the co-organiser, which means, with the micro-logic of small presses, that Camilla herself was. ‘The South West Poetry Tour is curated by Camilla Nelson and SJ Fowler,’ we are told. Full documentation of the tour, which includes videos of every performance, may be accessed here: https://www.theenemiesproject.com/southwest Spend a minute or two scrolling through the different combinations, enjoying the variety, or spend many hours looking through the lot!

You’re back. Good. Let’s watch Camilla Nelson reading a collaboration with JR Carpenter. They are well-matched. I have a whole batch of little topographical self-published pamphlets by the latter from when she read at Storm and Golden Sky, not unlike some of the works of Nelson’s Singing Apple (‘a small independent press devoted to the material investigation of poem production in relation to plants’, a blurb says). The video begins without introduction, but I’m guessing that the text is called something like ‘Many Reasons for Planting Trees’ (the first and last lines) and it repeats a chorus about ‘propagation’, and the changing seasons, which might be thought of as its poetic focus. It sounds as though there is some found text at use here (maybe all of it is). When one of the speakers reads of her ‘apple-shaped interior’ we sense that the socius and the self and the environment are being related to one another in a Guattarian way for this collaborative eco-poetics. The (female) voices are well-matched (I can’t distinguish them, despite JR’s Canadian accent). It’s good. All in all, a successful collaboration in the ‘Enemies’ mode, even a model. Watch it here: Video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=89DXuh2mvIA&feature=emb_logo

Notice that the two readers, despite the text being about physical growth, sprouting, blossoming, fruiting, are immobile, other than the ‘mobile’ phones they read from, as still, in fact, as the Barbara Hepworth sculpture next to them, a third collaborator, one might almost say! This isn’t a criticism. They don’t even have microphones as an excuse (I like to move a bit when I read and find microphones constraining and, often, unnecessary; I need to be miked up, like the late Miles Davis; that’s the trouble with looking at YouTube, you get distracted and watch other clips.). The screens they read from are small. They need to concentrate. They do. The uniformity of voice partly derives from this concentration.

The text that Nelson and Fowler coauthored could have been read in this way. Its thematics about notions of self, self-disclosure, and ambivalent violence is largely a psychological affair, despite the language of (will towards) movement and copresence. Two writers side by side reading a collaborative text is an adequate image of copresence. (Social undistancing, to refunction the contemporary jargon.) This is not what we get. Instead, we receive ‘a reading performance, read while dancing / wrestling,’ according to the note in Nemeses. (291)

The text (I listened without watching) is not identical, either due to later revisions, performance improvisations, or ‘live edits’, possibly caused by the disruptive movements during recitation. I will not focus on textual variations largely because it is impossible to judge the reasons for them. I doubt whether you will be surprised to see that Steven Fowler read the left-hand poem, Camilla Nelson, the right. (You can read that back onto the reading of the previous post if you wish, HERE, and, for economy, I will do so in my final analysis.)

Let’s watch it; it’s only 5 or so minutes long (the usual ‘Enemies’ limit, to ensure evenings aren’t unbearably long.): Here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-rn4ZGsziM&feature=emb_logo

The basic trope in this performance of ‘When the Rules Keep Changing’, I mean, of all elements except the recitation (which they attempt to read ‘straight’), is that the rules of two voiced collaborative performance, turn taking, for example, and immobility on the part of the non-reader (the kind of thing we see in Nelson’s duo with Carpenter), keep changing. The two poets interfere with one another, generate what communication theory calls noise to interrupt the message. What’s that quote from Benjamin I use as a preface to my book Unfinish? ‘Interruption is one of the fundamental devices of all structuring’. If so, in the larger formal entity of the performance as a whole, these actions are constitutive. However, they are not abstract interruptions (such as sudden noises, actions without motivation, DADA stuff). They are mainly (though not all) recognisable social signs of deliberate irritation at the other (which is reflected in the text). This includes Fowler flicking Camilla’s ponytail, looking out the window, reading with a back to her; and Nelson moving Steve’s microphone, stopping his picking his teeth (a silent ‘Don’t do that!’), and so on. They are visibly niggled by the other! At one point we see Nelson reading with Fowler standing too close behind her. (I am reminded of something Hilary Clinton said about the way Trump deliberately did that to menace her when she was speaking during the Presidential debates.) Later, when it involves wrestling, SJ carrying Nelson round the room, behind the audience (which is visibly laughing, slightly nervously), or Nelson jumped on Fowler’s back, it is more obviously ‘a reading performance, read while dancing / wrestling.’ (291) You notice Nelson is barefoot and dressed for dancing (and looks like a dancer) whereas Fowler is well-known as a wrestler and cage boxer. Nelson tucks the text in the back of her waistband so she can move, a clearly premeditated strategy. If you had any doubts, you realise that this has all been pre-planned, which is not to say that it doesn’t have an element of improvisation.

What I say of the end of the text, on the page alone –

The section (and the poem) ends with an image of asserted knowledge and safety:

the birdshave eaten all the breadcrumbs but I know the way.Held close kept safe. A flame stilled long enough

The movements of the ‘game’ of the whole coauthored poem’s ambivalent adversarial gestures are brought to temporary pause ‘long enough’ for illumination,

is enacted by Nelson reading these last lines on her own while Fowler kneels before her in an attitude of supplication or submission. Game over.

I’m not suggesting that there is a general conclusion about performative elements as they appear in collaborative texts to be drawn here, but it is clear there is an observable relationship between text and action. Remember the importance of the isolated word ‘live’, when Fowler talks of Nemeses demonstrating collaboration as ‘the making of challenging and complex work, live.’ The ‘text’ of the total performance is a multi-systemic act-event that only the reader as witness can put together. This occurs at exactly the point where the reception of the literary work as an act-event (in Derek Attridge’s terms) opens the whole thing out to a multiplicity of intersubjective assemblages, a co-creation of many minds beyond the two performers. That’s what’s happening here.

*

For comparison, it is worth watching: Óvinir: London - SJ Fowler and Ásta Fanney Sigurðardóttir, also recorded in 2016, for a different take on ‘wrestling’ collaborative poetry: Also: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TE162HrChrM

During the writing of this response a package has arrived. It contains Camilla Nelson’s KFS publication, Apples and Other Languages.

Remember, all posts in this ‘Collaboration’ strand may be accessed via links at the end of the first post, a hubpost, as I call it, here:

https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2020/01/robert-sheppard-thughts-on.html