anselm hollo 1934 – 2013

(Image by Alexander Kell – taken in London 2012)

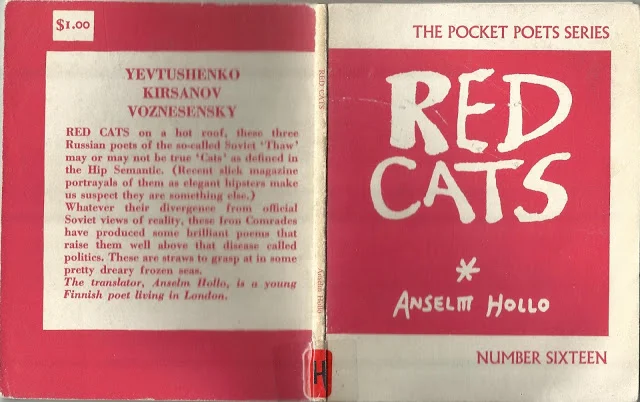

I cannot pretend I knew Anselm Hollo. I met him just last year, in what would be the last months of his life, which ended a few days ago. I witnessed one of the last readings he ever gave, if perhaps actually the very last, at the Horse Hospital in Bloomsbury. I helped organise the reading and I had the chance to spend an afternoon with him. Even if I cannot say I knew him really, I met him, and before that meeting, and I am sure for many years after it, he will have a presence in my life through his poetry. For there are bonds between him and I, and it is my opportunity now, in the wake of his dying, to make them real in the act of a thorough, if primarily private, recognition. This is a man who wrote through his life – who skewered life with his work, who affirmed his being alive in poetry, and made things new there too. Anselm Hollo was a viking – he looked like one, he wrote like one, and I am told, he often lived like one. He published over 40 books, and untold numbers of translations into and from Finnish, German, Swedish and French. In 2001 he was elected the United States anti-laureate. He lived for 78 years, and for over 60 of them, he wrote.

His life was one of breaking new ground, both in the literal ashes of post war Europe and in the redefinition of what poetry might do to us and for us. He also came to stand for the singular role of what a poet might pursue – to evidence a new kind of holistic understanding – as a translator, with a reach beyond single cultures and ‘great’ figures, as an anthologist, who is a collector of specimens and not a accountant of poetries, as an editor, a teacher, an organiser, a friend to poets and a community in himself. He was completely unique in his voice, instantly recognisable, eminently witty, underhanded, profound and disarming. He was gifted in understatement and ethereal profundity. He was prolific and generous. He was a poet’s poet.

And as many of us writing now are the underlings to his achievement, so he dragged with him so much from a past that might’ve otherwise been occluded or lost in the rearranging world of his youth. Finland, always a place of quixoticism, of underappreciated extremes, spent the better part of its modern history under Swedish yoke, and the great scholars of the fin de siecle, like Hollo’s father, rode a wave of pioneering linguistic and cultural reconstruction, of archiving, of repatriation. Hollo was a child of this movement, perhaps the most important literary Finnish traveller who ever lived, for he took this spirit of newness, of cosmopolitanism, of national energy to the world, unable to leave behind the dryest of Nordic wit and poetic noir. Unwilling to let go of his propensity to admire and inculcate mishearings, misspeakings, mistranslations, he offered this gift to poetries in Germany, England, and America. This is a man who moved to Germany during the immediate post war period, then fled to England when it became too stable, and then again ditched London in the 60s for America. This is a poet who spoke his time in his poetry, who chased it down.

Returning from his last trip to his old home in London, where he was amongst some of his finest friends and peers, those who we can now only envy and take inspiration from for their innovation and energy and daring, he faced the kind of battle against ill health that even his near indestructible constitution could not hold out against. His name lives on in the children of his great contemporaries, more than one of them being blessed with the name Anselm, and we should take time in the wake of his death to mark the passing of a generation that began much of what we might hope to continue, so that we don’t err into thinking we are original while in the shadow of those who have done it all before but have just been stupidly neglected, so that we can build on what took a lifetime to produce, and so that we might try to write well, because Anselm Hollo wrote well. He was an immensely good poet and it is a loss to the world and to poetry that he has died.

You can watch the reading he gave in London last year here

I significantly recommend you buy his books.

your friend

By Anselm Hollo.

he said this

he said that

when pressed

as to which

he said nothing at all

in his country the weather

was mostly rainy

he tried to ride horses

they didn’t go or went

too fast

he punched them in the head

he fell off them

he tried to love women

tried to write poems

even his fellow men

their wives their children and cattle

he tried to love

but he didn’t know

how or what was

or was good for him

at all

whatever it was

it kept punching him

in the head to make him

fall off

so he blamed them for it

all of them fellow men women

children cattle poems and horses

many a rainy

day you could hear him

yelling ‘it’s all

your fault’

after that things

were all right for a while

until the next try

Ten British poets read from Maya to honour the passing of Anselm Hollo

I really wanted to organise a reading to mark the death of Anselm Hollo, whom I admired so much. This was the feeble gesture I had to settle for, but the readings from these wonderful poets are uniformly beautiful.

And How It Goes by Anselm Hollo (I miss him)

Beyond the sadness of losing Anselm Hollo as a human being and a poet, his death has grown into something that continues to have significance for me because in his work I find an intense feeling that he lived how I live, through his writing, but 50 years ahead of me. Obviously there are enormous differences, none more so than he was a finer poet than I'm ever likely to be. Yet his work possesses a sense of place and a sense of humour, and trickery, and darkness, that I seek to possess. I've read so many poems of his in the last week that have made me feel a little overwhelmed that I have been to these places and hope to do these things, in life and in poetry. The people around me whom I love seem to be echoed by those he loves. He seems to have walked London as though it would not be his for long, as I often do. He dedicates poems as I have done. He has energy for new relationships, for endless writing, as I do. Now he is dead, 40 years on from writing these poems that have moved me so. It doesn't make me very sad, just makes me feel the inevitability of life and makes me appreciate how much my life is full of warmth and health and lovely humans, and lovely things, like poem below. For my friends!

And How It Goes

by Anselm Hollo (1967)

Zoo-day, today

with the 2 young

"What animal

did you like best?"

"That man"

She's three, more perfect

than any future

I or any man

will lead her to

but now, to the gates

and wait for the boat

by the Regent's canal

we stand in a queue

all tired, speechless

A line from Villon

sings into my head:

"Paradis paint"

"A painted paradise

where there are harps and lutes"

Yes and no children

but who say such pretty things

for me to inscribe

in one of my notebooks

with the many blank pages

marking the days

when I feel as forsaken as

balding Francois

who also found

in himself

the need to adore

as different as my stance is

here, in a queue of mums & dads

down the green slope

to the canal

- when he wrote to the Virgin

hypocrite, setting his words

to the quavers

of his mother's voice

le bon Dieu

knows where he'd left her

At least

I'm holding her hand

she's here, my daughter

he is here

"my son

the lives of poets

even the greatest, are dull

and serve as warnings"

To say this, suddenly

here, in the queue

would no doubt be brave

He's half asleep,

clutching a plastic lion

"The thing is, they could not

get out of themselves

any better than these

who also wait

for a boat

- o that it were drunken

on what wild seas -

they didn't

even try, just griped about it

or made little idols

for brighter moments ... "

The boat has arrived

and there,

the elephant's trumpet

farewell

Her weight on my knees

His head on my shoulder

here

we

go

We, best-loved animals

one, two, three

and as illuminated

as we'll ever be

Hollo the prophet

Every morning since Hollo died I've read his work (many of his books, but all of the indescribable Sojourns collected poems volume) on the tube, going to woerk, on the central Line. I've already written about how this work has had a profound affect on me, how personal it has become, how I feel his work like a ghost around me in this city. Now starting to read other poets for the first time in what feels like a long time, I have the sensation there are other things at play. This poetry has done something to me poetry has not done before. I don't know what that is. The humour, the trace of Scandinavia is in there. I'm sharing this work with people I really care about and they are feeling it too. Some snippets

whatever these two do

is interesting

round lamps of cells grow

up to lover porridge later

switch then to sleep now

the flying foxes swarm out

great its flurry time

watching the spectacle of the money

come to an end

things become clear

the energy of the world has grown tired

of our green &

bumbling

bumbling miniature world tree

in our front room

at times it seems merely a question of how to abdicate

the dashing biologist

“with the looks of a viking”

but really my parents

you were giant white rabbit people

one worries about the future of bears

in public in one house

this is known as a poetry reading

then one proceeds to drink gallons of cider in public

this is known as getting cracked

in love we loaf

munching love’s leaf

it is a fortunate condition

it is a pre-occupied porcupine

going about mother maya’s business

ah anna bloom

sweet ginger muff

the world seen as a huge inpenetrable

granite arse

el che is dead long live moomin troll

the elephant fell in love with a milimeter

francois villon was beautiful people

he went around treating people like shit

didn’t marry him ‘only to sleep’

but does now

sleep

they drowned my puppies

so I drunk a lot of vodka

there’s none could cure you

of your ignorance

I mean that’s great

we love you as you are

here

in the upper devonian sea

life is quiet

tumbleweed

looks like the skeleton of a brain

if a brain had bones

a bear, I thought

not one minute of my life have I wasted

a joyful summit of old savages - april 2012

There is a sense that poetry, or poets as a community (whatever that may mean), is unusually guilty of not appreciating those from previous generations who have the bad grace to remain alive beyond the first stay of their influence. Obscure in life is often followed by cult status in death, as though the poet’s inability to question interpretations of their work somehow qualifies such interpretations to take place. I would suggest this is hardly any more true of poetry than it is of almost everything in life – once gone, soon forgotten, until expiry somehow enshrines memory and allows an individual to focus comfortably on what is now static. Perhaps this is a beautiful thing – the maintenance of a resolute sense of change, with or without our permission. Poets however, do leave something which does not allow for such vagaries, and that is their poems, as concrete a record of their life as there is, which will often live long beyond them. But before that comes to pass, there is the opportunity some might view as a responsibility, for those who belong to a new generation of poetry, who are still being shaped, by their forebears as much as anything else, to reach out and connect with those who have come before, if not to learn from their practise and their experience, then just to sit back and watch how it is supposed to be done.

On Wednesday April 18th at the Horse Hospital in Bloomsbury, London, a privileged few were on hand to witness a rare occurrence that contradicted the often maudlin passing of the older generation. Four great poets who came to prominence in the 1960’s and have all maintained a relentless, brilliant and imperative writing practise in the fifty years or so since, read together, in reunion, with great humour, dignity, intelligence and generosity. Their mastery of poetry and their affability of manner provided the many in attendance, poets and readers of poetry what alike, an example of what might be the fruit of a lifetime spent as a poet – honest to conviction, ever humble in the service of is new, and what is exciting, about writing and reading poetry.

Without cynicism or fatigue, all four poets displayed an authority and a contentedness that represented the ubiquitous and almost taken for granted width of their influence. Not a single member of the quartet began writing to show those in the 70s, 80s, 90s, 00s and 10s what was possible in poetry, what could be achieved, what could re-understood, re-heard, reborn, and yet all the more for their sense of it being just about the poetry itself, they have continued to impact those lucky enough to witness, read and follow their work

As Anselm Hollo read William Carlos Williams, poems written just ten years before his birth, as Gunnar Harding recounted his time in the Swedish mounted cavalry, as Tom Raworth casually, and gently, evidenced again why he is the greatest living British poet, and as Andrei Codescu lamented the Gulf of Mexico oil spill in kind with the end of secrets in the modern age, one could not help but get a sense of the inability to perceive just what they had collectively achieved, across hundreds of collections, thousands of readings and more than a dozen nations.

If it was true, as was said and probably is the case, that these four men will never again share a stage, then all the more do we benefit from taking a moment in their collective presence to consider what it is all for – the practise of being a poet, reading poetry, attending readings, living with a pen in our hands. It is just about the poem, and being honest to that poem, amidst the same responsibility as everybody else, to be a decent person, one who will help those coming after them with a selflessness and a generosity that belies any notion of the poet as some pretentious conduit for some pseudo-muse in a lofty tower of god given talent. It is precisely this harmful notion that these four men have done so much to destroy, to prove that poetry comes from a lived life, from wide reading, from being a person as well, if not before, being a poet. And should any poets from my generation achieve half of what these four have in their lifetime, they will indeed be counted among the very few.