EUROPOE

Groundbreaking poetry by sixty of Europe’s most original poets, translated into English, brought together for one remarkable anthology.

Kingston University Press (May 2019) Available to buy here enemiesproject.bigcartel.com/product/europoe 143 pages. Paperback.

This was a labour of love. Perhaps the word labour might flash red here. It has been designed to be connected to the European poetry festival I run and to be fundamentally ephemeral, as I’m not really into being an anthologist, as I believe it’s a vocation, a real commitment (see Jerome Rothenberg) and I don’t have that in me at all. In this case I choose the poets from my own tastes and contacts, so they are (obviously not, but in a deeper way) not representative of anything but that and I asked each poet to negotiate their own choice of poems / translations / translators / languages / methods / appearances with me. I hope the book proves exciting to those who read it, that’s all I’m after.

“Celebrating the grand resurgence in literary and avant-garde poetry that has marked the 21st century in Europe, poets from over forty nations present works developing the lyric, sonic, visual, abstract and conceptual traditions. A volume that seeks not to offer a taxonomy but a brief glimpse of the brilliance of so many poets working at the forefront of the language arts, this is a book unified by a fidelity to that which is truly contemporary, amorphously continental and generously innovative.

Featuring poems by Pierre Alferi, Tomica Bajsić Aase Berg, Volodymyr Bilyk, Cecilie Bjørgås Jordheim, Ida Börjel, Serena Braida, Kristian Carlsson, Sophie Carolin-Wagner, Theodoros Chiotis, Iris Colomb, Efe Duyan, Federico Federici, Orsolya Fenyvesi, Mária Ferenčuhová, Frédéric Forte, Lies Van Gasse, Pavlo Grazhdanskij, Ana Gorria, João Luís Barreto Guimarães, Max Höfler, Niillas Holmberg, Zuzana Husarova, Maja Jantar, Ragnhildur Jóhanns, Aušra Kaziliūnaitė, Frank Keizer, Anatol Knotek, Amadej Kraljevič, Gabrielė Labanauskaitė, Morten Langeland, Luljeta Lleshanaku, Léonce W. Lupette, Christodoulos Makris, Maria Malinskovskaya, Ricardo Marques, Immanuel Mifsud, Simona Nastac, Bruno Neiva, Eugene Ostashevsky, Eiríkur Örn Norðdahl, Daniele Pantano, Astra Papachristodoulou, Cosmin Perţa, Jörg Piringer, Inga Pizane, Tomáš Přidal, Monika Rinck, Cia Rinne, Jon Ståle Ritland, Ekaterina Samigulina, Martin Glaz Serup, Ásta Fanney Sigurðardóttir, Muanis Sinanović, Morten Søndergaard, Esther Strauß, Kinga Toth, Nadia de Vries, Krišjānis Zeļģis.

EUROPOE, edited by British poet SJ Fowler and presented by European Poetry Festival in the UK, showcases those who are often on the margins of their own nations literary culture, precisely because their work is forward-looking and challenging, alongside some of the most renowned names in Europe. EUROPOE is an anthology as a unique document of poetry, marking a moment in time for a modern, and thoroughly European, means of experiencing literature.”

A review of EUROPOE by Andrew Hopkins - July 9th 2020

https://andyhopkinspoet.wordpress.com/2020/07/08/europoe/

This anthology that came out last year is an inspiring foray into the possibilities that the page offers. A flick through Britain’s poetry magazines might lead you to believe that UK poetry is in the slough of despond. There are one or two journals and magazines that still come through my door that only drop on my doormat because I keep forgetting to cancel them. This is not to say that there isn’t energy and experiment in UK poetry: there is; it’s just that (as there is in every day and every age) good people without audience, and rubbish people packing out venues pre-covid.

So this anthology is an excellent place to start for anyone who has leafed through a UK poetry publication from the last twenty years and thought ‘ Is this… it?’. Whilst I am so tempted to take pictures of the poems in this anthology that would completely spoil their discovery for you. You should buy this anthology from here: https://www.europeanpoetryfestival.com/europoe, and you should probably do it now.

As the editor SJ Fowler makes clear on one of the Penteract Press podcasts, some of the poets in this anthology are famous in their own countries – more famous, in fact, than ’emotion’ poets (see the podcasts for details). There are some quite complex reasons for that – and best left for another time, but there is an analogy to be made with the music crassly dubbed in this country as ‘Krautrock’ by the music press: this was the music played by bands such as Neu!, Popol Vuh, Can, Kraftwerk, etc coming out of Germany and other countries in the 60s/70s. This music saw that the ‘old’ music forms were tainted with ideologies they didn’t agree with – so sought new forms, new ideas. It is James Fenton, I think, in a book from 2004 that I do not have to hand who says that writers committing themselves to free verse do so at their own peril: they are attaching themselves to an ideology they may not be aware of, in a crowded field. Surely we could make the same point of he samesame writers who took Fenton’s advice.

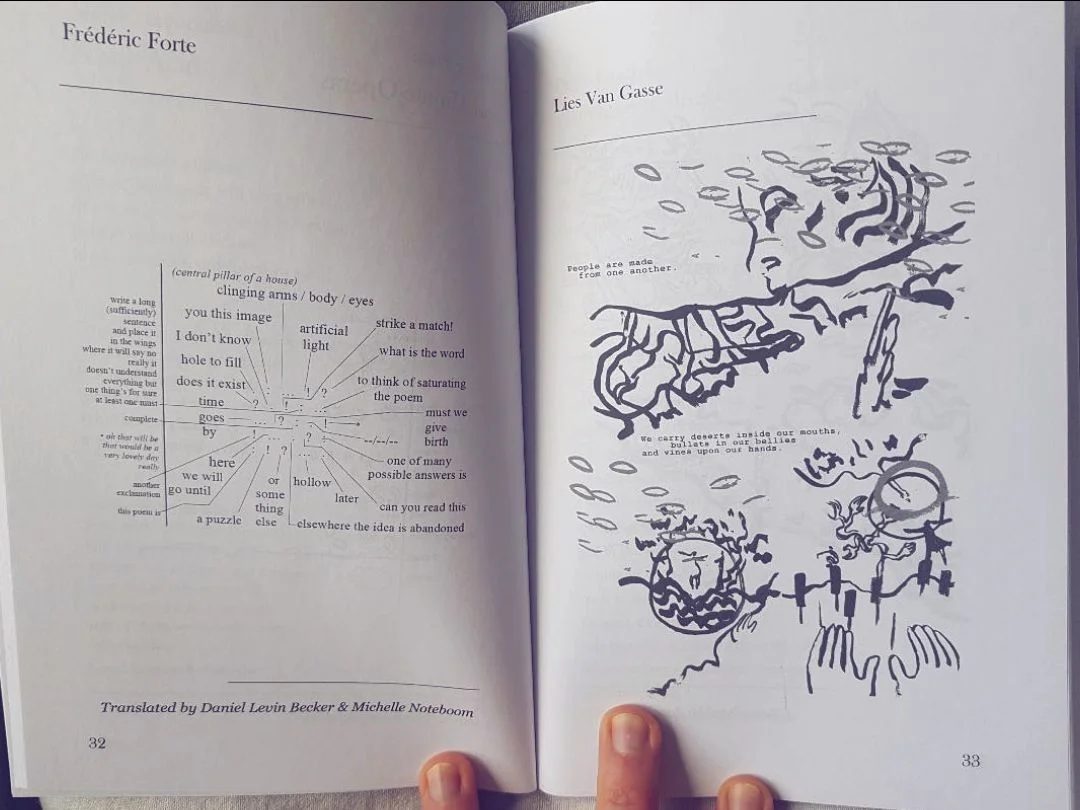

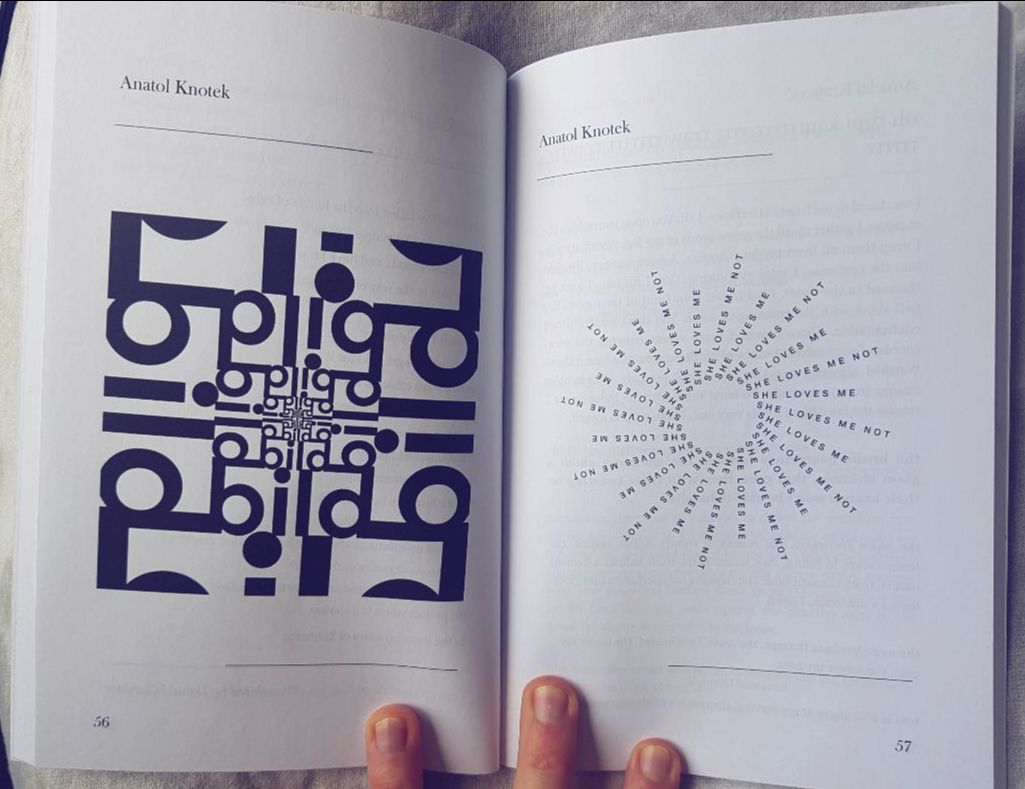

Anyway, to the poems. This anthology covers a huge range. It goes from poems that convey with language, to poems that are made of language, to poems that are made of no language. Personally, the more that the envelope was pushed, the more I liked the work. People have been making experimental poems for as long as people have been making poems; stop me if you’ve heard me say this before, but a border ballad is a pretty experimental poem, actually, from the oral tradition. Literate creators have been experimenting with written form for a very long time, too. So the writers collected in this anthology are adding their poems, brick by brick, to a venerable cathedral of work. Many people will tell you that ’emotion’ isn’t the point of experimental poetry, but it happens anyway: the most successful experimental poems hit your emotions first, before they can access your rational thought. For me, the more experimental, to more refreshing and the more inspiring. But there has to be more that just ‘refreshing’ – otherwise the work is so context dependent that in the future the experiment is ‘ruined’ by the way that future readers have made this discovery themselves by reading backwards through copyists towards the originals. It also has to be more than self-negating, too: so that the poet’s constant drive towards the new experiment doesn’t rob the old experiments of their value. The asemic and abstract work that I liked best in the anthology is work that will always have a power – even when the host language is no longer spoken.

The anthology isn’t only made up of ‘graphic’ challenge in terms of form, though. A large amount of the work is not a shock to the eyeballs when you turn the page. But there is, in European poetry (to generalise hopelessly) a greater willingness to pull the reader further between lines, between clauses, or between stanzas. So in Theodoros Chiotis’ ‘Sea Pictures’ the second stanza takes us across the two lines ‘Letters and words turn into long galleries/ vats of acid are now stored underneath the living room table’. Name me a well known poet writing in English that would go so far – across so many different noun areas? Nouns that have NOT come up in the poem before and are not naturally linked to the previous images. The third stanza then opens with ‘Parachute material identical to the carbon make-up…’, so our hold of the startling ideas of stanza two (on first reading) has to be relaxed as we move forward. The poem, though, has a spine of repetition and what you might call ‘tone’ or ‘mood’. Only the most spiting-their-own-face reader would not take something from the poem (with their nose bleeding in their hands). These poems are even ready for those readers – Chiotis even swears at you later ‘if you cannot fathom this’.

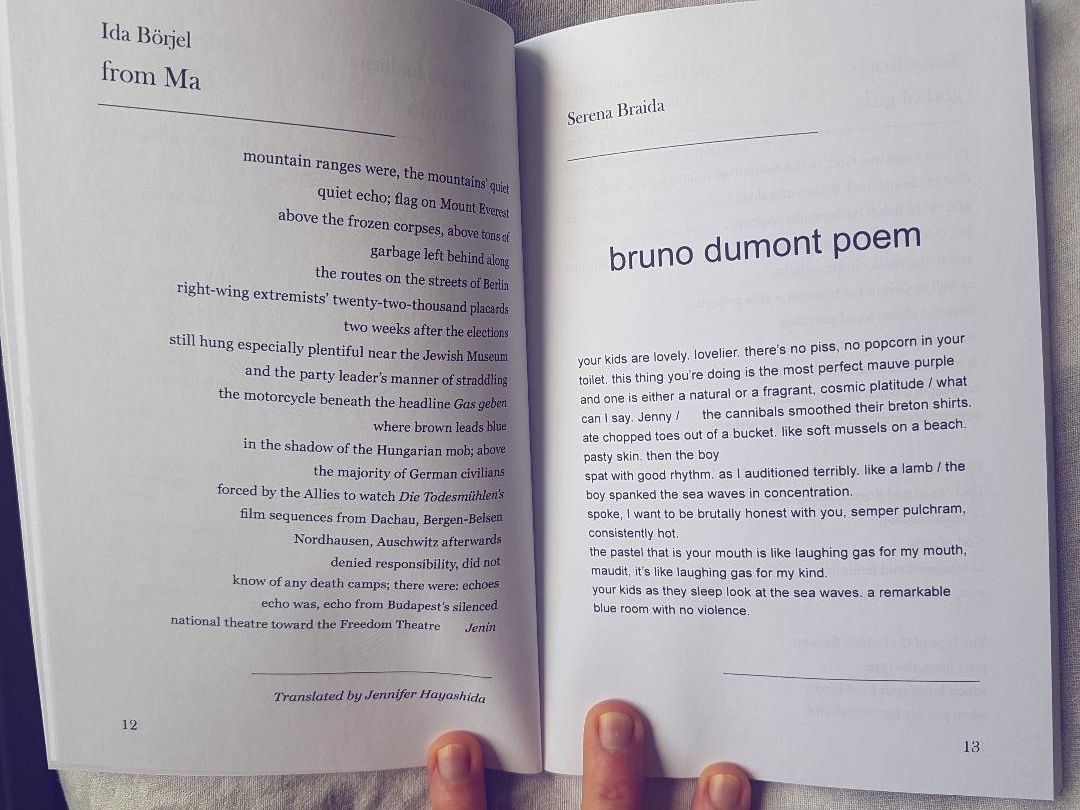

If I open the anthology at another page, Serena Braida’s poem ‘bruno dumont poem’ begins ‘your kids are lovely. lovelier. there’s no piss, no popcorn in your toilet. the thing you’re doing is the most perfect mauve purple’. This willingness to move the reader on within the sentence is difficult perhaps for me to convey. But it is perhaps easiest to say if I write that ‘to convey’ is not always (and in some cases not ever) the aim, but if grammar and syntax is getting in the way of an idea, then the conventions must be broken. Grice created a set of maxims of conversation by which communication was said to be possible; however contested they may be, it is worth looking them up.

The maxim of quantity.

The maxim of quality

The maxim of relevance

The maxim of manner

It’s also worth considering that the term used for going against these ‘maxims’ is called ‘flouting’ the maxims. The poems in the anthology that are not necessarily swimming in front of your eyes, are still taking the reader on braver steps across the arc of a whole poem. So these poems are ‘flouters’ of ‘quantity’ and ‘relevance’ and ‘manner’ and this allows the poets a greater amount of elbow room with which to pull response out of the reader (not room to browbeat the reader with intended meaning).

In his introduction, Fowler makes clear that it is his desire to ‘get out of the way’ of the subsequent pages and that editor ‘will always eat more grief than love’, but this anthology will start the reader on journeys of their own into the many forms and ideas that are in evidence here by the many writers involved. And that is worthy of huge credit.